While increases in life expectancy are good, increases in “healthy life expectancy” are better.

Unfortunately, health does not generally improve with age. Life expectancy is generally increasing around the world, which is good. But, it would be better if “healthy life expectancy” (the years we spend in good health as we get older) increased too. Carol Jagger, AXA Professor of Epidemiology of Ageing at Newcastle University in the UK is studying the factors that could help us live both longerandhealthier. We have a certain amount of control over some of these factors – for example, having an upbeat attitude to life, eating better and exercising more. Some others, of course, are not always in our hands – examples here include socioeconomic factors like education and wealth.

Jagger’s research is based on analyzing data from the Cognitive Function and Ageing Studies (CFAS) project, which followed people aged 65 years or above in three centers in England (Cambridgeshire, Newcastle and Nottingham) between 1991 and 2011. There were 2500 participants in each center. This data provides prevalence estimates for three health measures: self-perceived health (defined as excellent-good, fair or poor), cognitive impairment (moderate-severe, mild or none – as assessed by the Mini-Mental State Examination score); and disability in daily living activities (defined as none, mild, or moderate-severe). She calculated health expectancies for the three regions combined using the so-called Sullivan method.

Carol Jagger answers our questions:

Why is studying healthy life expectancy, as opposed to just life expectancy itself, important?

“The last century saw huge changes in life expectancy around the world. The result is an increasingly ageing population and particularly numbers of very old people – that is those aged 85 years and over, who are the fastest growing demographic in many countries. We know that getting older means more health problems but life expectancy is only a measure of the quantity of life lived. Healthy life expectancy (HLE) on the other hand gives us information onboththequalityas well as thequantityof years lived. This measure is especially useful in answering the important question of whether those extra years of life we are seeing are good/healthy or not.”

Living healthier as we age is not only important for us as individuals, but also as a society. Ill health places a burden on families and caregivers, the social security and healthcare system of a country, as well as pension funds, both public and private.

Your studies show some important differences between men and women when it comes to HLE?

“In most countries, women live longer than men. However, since women’s HLE is generally on a par with that of men’s, women tend to spend a greater proportion of their remaining years unhealthy. What is more, recent research from both the UK and US suggests that, at least in terms of disability-free life expectancy, women are losing ground to men.

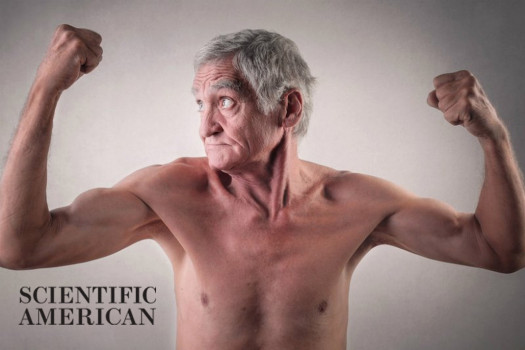

“Over the 20 years between the two CFAS studies (CFAS I and II), we found that men’s LE at age 65 increased by 4.5 years and women’s by 3.6. However, for men, over half of this increase was in years free of disability (2.6 years) whilst women saw only a 0.5 year increase in these years.

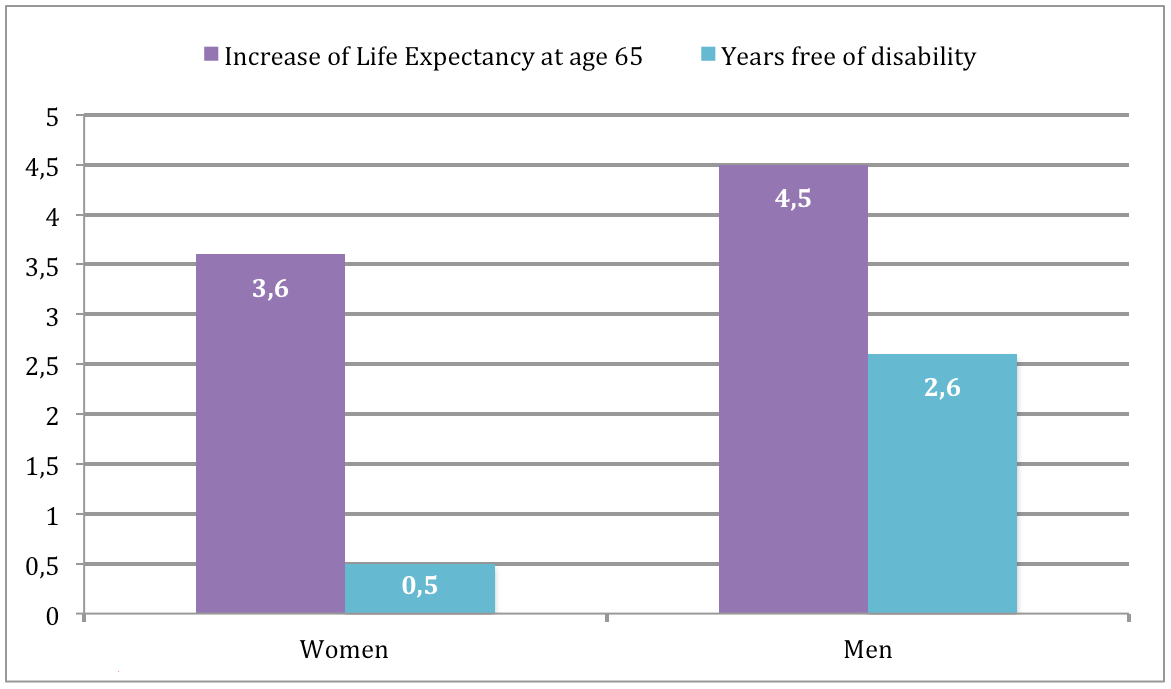

“In a similar US study that reported changes over a 30 year time span from 1982 to 2011, men’s overall LE at age 65 increased and the proportion of life spent free of disability rose from 78% in 1982 to 81% in 2011. In contrast, women enjoyed much smaller increases in LE and the proportion of life lived without disability remained at 70% over the whole 30 years.

Between CFA I and CFA II - Period of 20 years

US Study : Proportion of life spent free of disability

“Some of this increased disability for women comes from the fact that they tend to suffer from more diseases and health conditions, particularly non-fatal ones like arthritis. Another study in Newcastle, the Newcastle 85+ Study, recruited a cohort of over 1000 men and women born in 1921, aged 85 years at first interview, and followed them up for five years. At age 85, women had on average five diseases compared to men who had four.

“But it’s not all doom and gloom. For both the UK and US, however, increases in disability were, at least, in less severe form. Our study also showed positive results for mental health in that, for women, all the extra years were free of cognitive impairment.”

Are cognitive and physical disability related as we get older?

We generally measure disability by the degree of ability to perform daily life activities (ADLs) without difficulty or help. Basic ADLs involve personal care, such as bathing, going to the toilet, dressing and getting in and out of a bed or a chair. Activities that tap less severe disability, and known as instrumental ADLs, are those required for maintaining a household – for example, doing the shopping, laundry or making a hot meal. Many of these require both mental and physical function, but activities related to cognitive abilities are typically managing money and medications.

Someone who cannot dress unaided, for instance, might be cognitively impaired, which means they might dress inappropriately without help, or have arthritis, which means they cannot do up buttons or zips. But, cognitive and physical function are also related because they share common risk factors. One good example is obesity, which increases the risk for both dementia and arthritis.

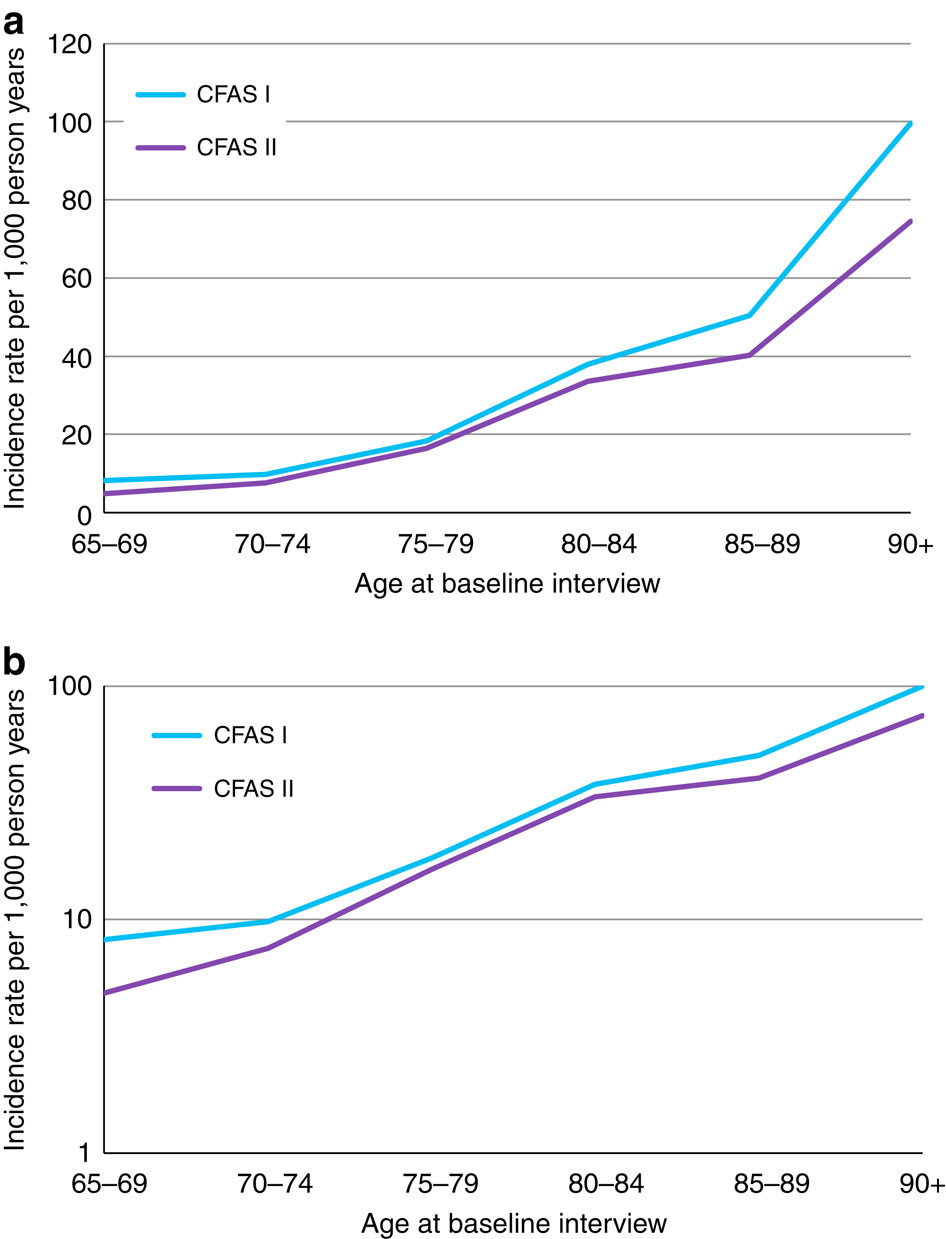

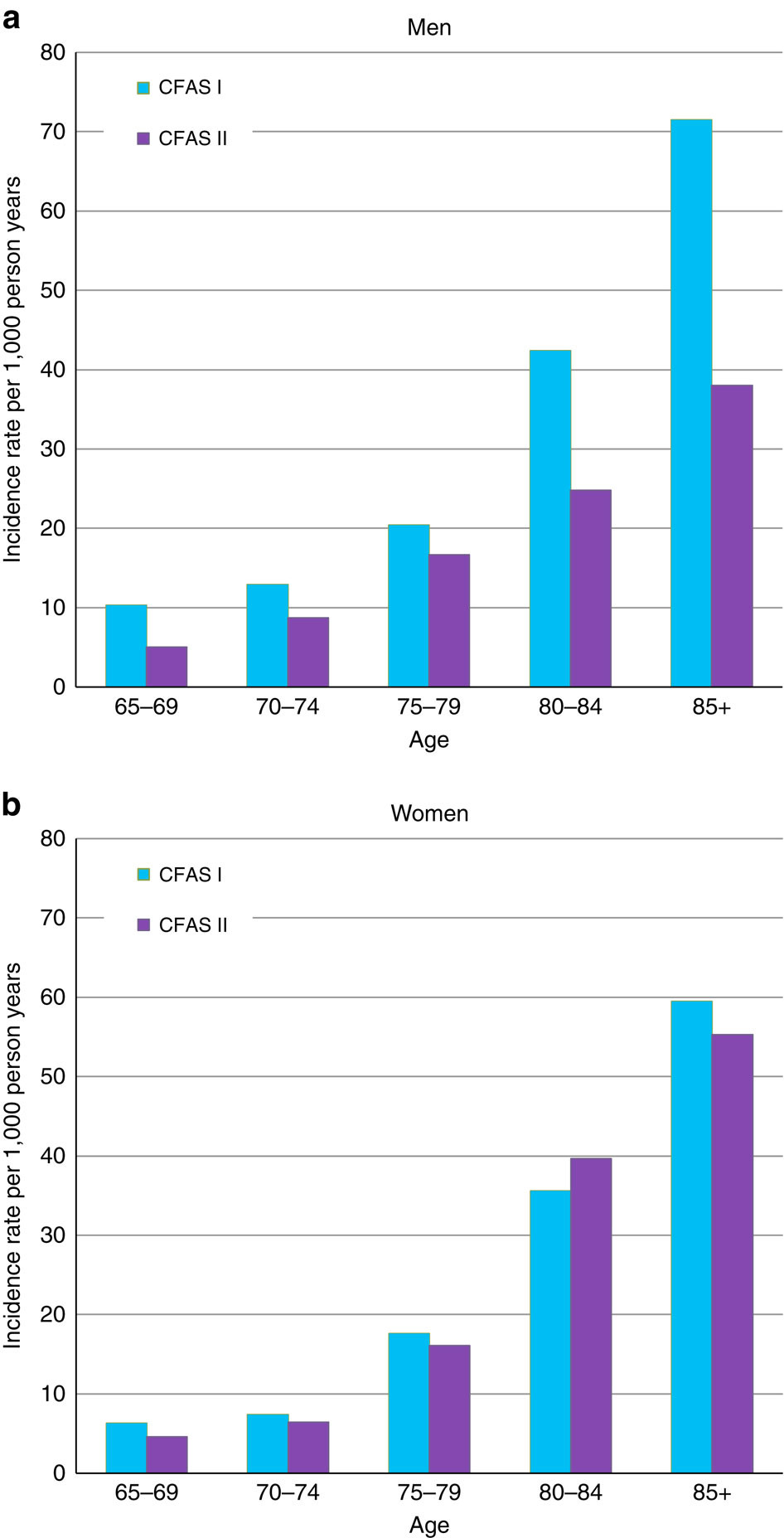

Importantly, cognitive disability or dementia are not inevitable as we get older. Research from the CFAS studies has shown that not only has the prevalence of dementia reduced over the last 20 years but the most recent work finds the incidence (the proportion of people developing dementia in a given time period) has fallen by 20%, albeit mostly in men rather than women.

Dementia incidence rates in CFAS I and CFAS II. (a) Incidence rate of dementia per 1,000 person years in CFAS I and CFAS II by age at baseline interview. Natural scale. (b) Incidence rate of dementia per 1,000 person years in CFAS I and CFAS II by age at baseline interview. Logarithmic scale. Credit: Nature Publishing Group

Dementia incidence rates in men and women. (a) Incidence rate of dementia per 1,000 person years in men for CFAS I and CFAS II by age at baseline interview. (b) Incidence rate of dementia per 1,000 person years in women for CFAS I and CFAS II by age at baseline interview.Credit: Nature Publishing Group

What role does a person’s education play in their HLE?

Early life circumstances, including education and even parental education are known to influence life health and mortality. People with lower levels of education tend to have more disease and disability and die earlier and some, but not all of this comes from later life disadvantages. In CFAS I, almost 75% of participants had only a basic education (0-9 years) with just 9% going onto to higher education (12 or more years of age). At age 65, men and women with the lowest education lived on average a fewer 0.8 and 1.4 years respectively and 0.9 and 1.9 years less free from disability when compared to people with the highest level of education. Things appear to improving though, since in the CFAS II, only 27% had 9 or less years of education and 22% had benefited from higher education. But education has a long-lasting effect. In the Newcastle 85+ Study, education was the only socio-economic measure that differentiated the different disability trajectories that 85 year olds had over the next five years, those with higher education being much less likely to be in the most disabled trajectories.

It will be interesting to see whether these inequalities in HLE continue as more data comes in.

Jean-Marie Robine, Research Director at INSERM, the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research, who also studies human longevity, is very pleased with the outcome of Jagger and colleagues’ research so far: “The CFAS study is remarkable because it spans a period of over 20 years and concerns thousands of older people. The collected data suggest that over time people older than 65 live longer with good cognitive abilities. This is very good news and obviously related to the improved education levels of successive birth cohorts.”

Source : Scientific American