J. Peter Burgess is a philosopher and political scientist who holds the AXA Chair in Geopolitical Risks, at Ecole Normale Supérieure in Paris. During AXA’s Security Days – an internal event that brought together AXA Group security teams to discuss the future of security – he discussed the relation between security and society, the recent revolution in security thinking, and how allusive the idea of security actually is.

Read below an abridged version of his remarks, and exchanges with the audience.

Security and society

What are we talking about when we talk about ‘security’? Well, let's start with the ‘we’. Who is that is that is looking for security for whom is security an important question? Security is a question for all different kinds of people – not just philosophers and political scientists. It is important for individuals and families, for the different groups and associations in society, for businesses and organisations, for national politics, and international relations. Each of these levels of security has a different ‘we’, a different kind of actor looking for security. Each one has different needs, different objectives. But they all face the same kind of problem: how can I prevent bad thing from happening in the future?.

When we do research on security, we start by asking how people understand security in their particular social setting. What are the things they value and what are the dangers that threaten them? What kind of assumptions do they have—implicit or explicit—about what is threatened and what is threatening? What are the political, social, economic, even ethical consequences of these assumptions? In order to answer these questions researchers study the arguments and concepts people use, the try to understand how people perceive their world by examining how they talk about it, what ideas and facts are important to them, how they assess what is important or not, what they think is under threat or not, where they think they can find security, and how they think they can avoid insecurity. As it happens there are huge and often poorly grounded assumptions behind the idea of security: ask any two people on the street and you get different answers about what security is. It becomes clear that security is not an absolute. It is a matter of where you are in society.

This is why, in order to understand security, we need to ask who is under threat, what is the threat, from what point of view are we threatened? What is actually threatened? And what does this threat give us the right to do?

These are all societal questions. Their answers depend on where we are situated in society, what social setting we find ourselves in, what kind of work we do, what kind of culture we come from, what language we speak, what religion we have, what region we live in, what country we live in, and what part of the world we are in. All these things, and many others have an impact on how we understand security threats, threats to our business, threats to our work unit, threats to our nation, and threats to our family.

We quickly see that the question of security is a question of society.

The revolution in security thinking

Until only recently, we thought of security as a matter of walls. Maintaining security was a matter of putting a wall—in one form or another—between us and what threatens us. The best image of this is the Medieval fortress. The massive fortress walls let us keep a sharp line between us and what threatens us. It was a bipolar kind of thinking based on a clear distinction between good and bad, right and wrong, beautiful and ugly, healthy and unhealthy, safe and dangers. This is essentially the security model we used until the end of the Cold War in 1989, when the Berlin Wall fell, as did the great bipolar divide between East and West.

The convergence of the two sides led to the emergence of a whole different class of threats and a different way of thinking about them. Suddenly, instead of a wall that assured a divide between us and what threatens us, the threat was among us. The paradigmatic example is terrorism. The threat from terrorism does not respect borders, does not exist ‘over there’, cannot even be identified in a way that would let us build a barrier defence. The character of terrorism is that the threat comes from inside society, from our street, our neighbourhood, our business, etc. There simply is no ‘outside’. The major attacks on European soil in the last two decades have been carried out not by foreigners from beyond the border but by European citizens or by people with valid residence documents.

COVID is another example of this kind of threat: it doesn’t respect national borders, even despite our border-closing reflexes. The same goes with climate change, environmental threats, cyber criminality, etc. The idea of doing security by keeping security threats out, by building firewalls or granite walls or any kind of walls, just doesn't work in these cases.

In short, Security is no longer a matter of us and them. It is a matter of how we live together in society. It is a societal question. So instead of building walls to keep up things out, we must think carefully and patiently about how to organise society to manage the unavoidable and enduring presence of threats.

In other words, it is not about preventing threats; it is about managing our relationship to others in society so that when the security event occurs, we will be ready. We will be resilient and robust. On a national or industrial level, in small businesses, in commercial units, wherever we are, security is about living together in the presence of threats, not about prevent them enough certainty and consistency to call it security. This is our new security landscape.

Security is not a fact

For all these reasons we can never say, factually, that we are now secure. For people who work in security, this is the reality. Security is a never-ending task for security operatives and experts because we can never know for sure when we have it. We can never know for sure what is around the corner, what is possible, or what might happen. Security is always about the future and never about the present. It is about what might happen tomorrow, next week, next month. It is not what we know in the present; it is what we can imagine about the future.

That is why imagination has become extremely important in security at all levels. The most important conclusion of the 9/11 Commission’s report on the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the US was that the most critical failure was one of imagination. Former US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld once said that the attack Pearl Harbor in 1941 that brought the US into World War II was also due to a failure of imagination. Indeed we can go so far as to say that the ‘cause’ of insecurity is our inability to imagine the future.

Therefore, facts can only help us to a certain extent. Of course, we would like to know what the security threats are. We would like to know what measures should be taken, but we can never be 100 percent sure about them. Therefore, we must rely on our intuition, our culture, our experience – on things that do not boil down to factuality and absolute rationality.

That is why foresight analysis is done – at AXA and elsewhere – by studying not only the facts, but also art and literature.

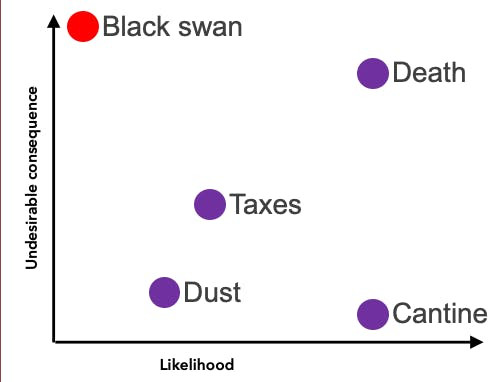

Such analysis is often done by correlating two metrics: likelihood and (negative) consequences. I’ve argued elsewhere that this method is fallacious and problematic for reasons we can come back to. We can visualise this using a graph that shows undesirable consequences on the vertical axis and likelihood on the horizontal axis. Let’s situate some examples: paying taxes, for example is relatively likely and relatively unpleasant so we can place it in the middle. Death is highly likely and highly undesirable. Getting stale bread in the canteen is quite likely to happen but with very weak consequences, while inhaling dust at any time is moderately likely and moderately low consequence.

Then we have the famous Black Swan: these are occurrences with very undesirable consequences but an extremely low likelihood of occurring. Other examples are 9/11, a meteorite, the 2008 financial crash, and Fukushima: they were all very unlikely, but they all had very highly negative consequences.

Naseem Nicolas Taleb wrote a book called The Black Swan, in which he talks about the impact of the highly improbable. His point is that even though these things do not happen, they change in their likelihood and undesirability when we start to think about them. The more we know about what a Black Swan is, the better prepared we are for it; socially, morally, and culturally, and thus the impact becomes lower.

Security is the science of not-knowing, and this is my conclusion. Paradoxically, the threat we most need to plan for is the one we cannot plan for. We spend countless hours and resources planning for the event that cannot be planned for it. It is a dreadful paradox that security researchers and security operatives are forced to work in.

What about an alternative approach? What about learning to live with the unknown? It is more effective and safer in the end to adopt a posture of non-knowing, of preparing society, our businesses, our communities, our families and friends to hold together when things get rough, on the quite responsable assumption that they will, at one time or another, indeed get rough. This might mean something like embracing more humility, embracing fallibility, embracing imperfection, embracing creativity, and embracing humanity.

Q&A session

How much time, effort, and resources should we devote to each one of the specific points in the Black Swan Event graph?

We do not want to spend all our resources on trying to find the black swan that never happens while overlooking something that might be more likely to happen. What is your recommendation for achieving balance on this point?

We can think in terms of two approaches, which map onto the two axes. To address the ‘undesirable consequences axis, we would want to adopt the kind of approach I idealistically mentioned in my conclusion’, i.e., human preparedness. This involves getting ready as human beings to face unpleasant things, which in turn means cultivating human characteristics like humility, creativity, solidarity, etc. Humility means not being arrogant and believing we can and should master all the catastrophes that come but being prepared to absorb them when they happen, should they happen. And on the ‘likelihood’ axis, we can to a far greater degree use traditional methods for trying to reduce risk by assembling data about it, by noting which measures have reduced the likelihood of occurrence in the past. This can help us reduce the likelihood of specific catastrophic events. But we can only reduce undesirable consequences and their impact by preparing as human beings. These are two completely different ways of managing risk.

Extending on your point and using this analogy, we cannot possibly put an infinite number of resources into looking at every single threat scenario available to us. Is the other side of the paradigm resilience? Is our Business Continuity Plan planning in effect to say we cannot address every problem. We cannot foresee every problem, but we know at some point we may need to use offsite backups or other emergency fixes. Is data resilience the other side of not being able to do that kind of infinite amount of risk analysis?

That is an excellent operational question that I am not very often confronted with. In a situation of limited resources, which of course is the situation of any business, the typical recommendation would be that resources should be allocated to both approaches – reducing likelihood and increasing resilience. However, shifting more resources to the latter, increasing resilience, may be useful. One advantage of the increasing resilience approach is that it is far more transversal. A small amount of transversal increase in resilience can lower the undesirable or negative consequences of all these types of undesirable events. Conversely, if one chooses the approach of seeking to lower likelihood you must focus on each potential event. The bad bread in the canteen has one solution, the dust problem has another, death has another again. And that’s inefficient from a resource distribution perspective. It is less efficient than the globally preparing human beings to face bad things approach. I am not saying all resources should be put into that approach, but that we could increase our efficiency in the long term by moving in that direction.

People have been predicting a major pandemic for quite some time. To what extent is the COVID-19 pandemic a failure of imagination as opposed to being a ‘grey rhino’ – i.e., something we knew was going to happen at some point but simply did not address?

This question has been debated among scientists and researchers. The answer is: it is both; there were all sorts of indicators out there, as well as smart people saying it was coming, including high profile people who had the microphones within reach. But there was denial as well. Not wanting to know or believe also represents a lack of imagination. I would call COVID-19 a Black Swan event in this sense. It was not real enough for us, even though as late as the early 20th century we experienced the third historical wave of the Bubonic Plague, and it looked very much like what we are seeing today, though it was (so far) worst.

I would like to ask about what could be the driver behind us as a society reacting to threats that come our way. I would like to mention the Ebola crisis of not so long ago, where basically as a world community we hardly did anything about it. I believe this is because it was in Africa, which is perceived as far away from us and thus extremely low consequence for us.

I share entirely your point of view. It is quite disconcerting, and a major reality supports your opinion. In the southern hemisphere, and in India, which lies between the north and the south, the effects of the pandemic are just starting. In Sub-Saharan Africa, there is not any kind of vaccination protocol in place. We have a global class system, and it is structuring the way we approach the pandemic. It is a matter of drivers or incentives. And of course, we produced vaccines for the US and Europe first. Once we were over the vaccination hump, we could start producing for others and address the needs of others around the world. It is a sad reality. And it is a senseless prejudice because pandemics are obviously global. If we do not battle it all around the globe, it can come back and hurt everybody. Even if you are not interested in the humanitarian aspect, it is not hard to see that we all benefit by making sure that Sub-Saharan Africa is also served. It is very much a question of the source of political will. Is it instrumental calculation or humanitarian conscience? I fear it is more the former and less the latter, for better or worse.

How do you deal with politics in security in this case? This is related to the issue of political will and how to get past those challenges.

This is the core question. In my writing and work I try to match my admittedly idealistic perspectives on the world and on security risks, which are hard to swallow for people who are worried about their bottom line or keeping political power. I try to pair a purely humanitarian approach with a pragmatic one: Your business well benefit if you give some space to a humanitarian approach. You will do better in your critical ambitions as a political leader if you give a humanitarian perspective some space. It is possible to make this argument. There is money to be made and resources to be saved by adopting a more humane approach to security risks, even in the very day-to-day work of insurance and investment management.

About Prof. J. Peter Burgess

J. Peter Burgess holds the AXA Chair in Geopolitical Risks, at ENS Paris. He is a philosopher and political scientist whose research and writing concern the meeting place between culture and politics, with a special emphasis on the theory and ethics of security and insecurity. He has held positions at the Peace Research Institute Oslo; European University Institute, Florence; the Centre for Security Studies, Collegium Civitas, Warsaw; Sciences Po, Paris; the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU); the Centre for Development and the Environment (SUM), University of Oslo; and the Neubauer Collegium of the University of Chicago. Professor Burgess has developed and directed a range of collaborative research projects with Norwegian and European partners, has contributed to the development of research policy as a consultant to the European Commission, and has collaborated in the elaboration of public policy in Norway, France, and Poland.

Other articles from the same author

Discover research projects related to the topic

Finance, Investment & Risk Management

Societal Challenges

Microfinance & Financial Inclusion

Emerging Market

Inequality & Poverty

Joint Research Initiative

China

2021.04.19

Understanding the Financial Lives of Low Income Households in China

Leveraging financial diaries research methodology, this joint initiative aims to provide actionable insights about the financial lives of low-income households... Read more

Xiugen

MO